By Juan Reyes

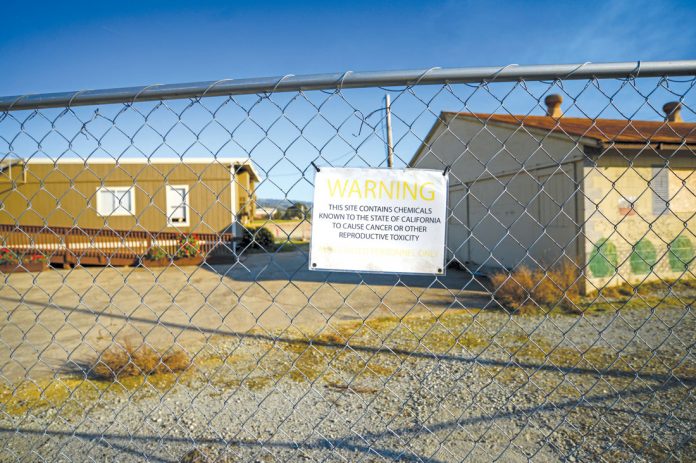

The Morgan Hill Unified School District is set to continue construction at S.G. Borello School after spending months removing contaminated soil off the proposed site.

Lanae Bays, communications coordinator at Morgan Hill Unified School District, said in an email that the soil removal process for dirt that contained pesticides is complete.

“Students in the area are fortunate to soon have a safe and modern neighborhood school they can walk to,” Bays said. “S.G. Borello school will alleviate some of the crowding in the nearby schools that are currently at capacity.”

The cost of the soil removal process was $1.7 million.

The new school site, which is located at Peet Road and Mission Avenida, will include about 27 classrooms for 600 students. It will be called S.G. Borello Elementary School in homage to the family that donated the property to the school district.

Construction of the new $20 million school is set to begin August. It will take an estimated 490 days to complete.

The school will be funded through the $198 million Measure G capital improvements bond along with developer fees.

The Department of Toxic Substances Control prepared a Removal Action Workplan (RAW) for the Borello site.

The RAW proposed that the school district needed to excavate and dispose of approximately 19,700 cubic yards of contaminated soil containing concentrations of pesticides, specifically dieldrin and chlordane.

The Environmental Protection Agency banned all uses of aldrin and dieldrin in 1974, except to control termites. In 1987, EPA banned all uses.

According to the school district, there was never an identification of the condition as toxic in the analysis of the soil make up.

Morgan Hill Unified claims the owner attempted to remediate the soil in 2005. The school district reassessed the soil prior to accepting the school site in 2017.

The school district determined that the bioremediation performed by the landowner in 2005 had failed to remove the prohibitive pesticides.

Bioremediation is like a natural cleanup of contaminants in the environment by eating chemical compounds that harm the environment. An example is microbes that eat oil and that have been used to clean up oil spills in the ocean. When oil-eating microbes digest the oil, they transform it into harmless waste products such as water and carbon dioxide.

The downside to bioremediation is if the microbes don’t have proper conditions of temperature, water and nutrients, they may not be able to digest the contaminants properly or effectively.

The California State Department of Toxic Substances Control determined additional remediation had to occur in line with state standards prior to building a school. Thus, the board determined that “the safest and most proven way to remediate the soil was to off-haul the soil rather than repeating the bioremediation which proved ineffective in 2005.”

The RAW included a list of major projects such as using approximately 1,600 truckloads—which comes out to 30 to 50 per day—to remove contaminated soil. The stockpiles were placed on plastic sheeting and covered before being transported to the Kirby Canyon Landfill Management Facility for disposal.

The cleaning crews also monitored for dust generated during soil remediation activities.

The remediation project was predicted to take time and the school district built a flexible schedule to accommodate any contingencies that might arise.

MHUSD Superintendent Steve Betando said in an email that the soil with the pesticides has been removed using the one proven method for remediation.

“The community should rest assured that the site is likely the cleanest land developed on plots that were once used for agriculture,” he said.