Centennial Series Mexican Governor Jose Figueroa gave Hernandez

title to nearly 9,000 acres of land that is now Morgan Hill

Editor’s Note: The following is the sixth installment in a series commemorating Morgan Hill’s 100th anniversary. The Morgan Hill Times is taking a trip back in time to 1906. From now through November, we will feature stories in Tuesday’s paper about the people, places and events instrumental in the founding of the city.

By Martin Cheek

Special to The Times

Morgan Hill – In the southern district of Morgan Hill there’s a thoroughfare called Juan Hernandez Drive. Most residents who pass by the street sign are not aware that Señor Juan Maria Hernandez was Morgan Hill’s original landowner.

His story represents a romantic but short-lived era of California history – the days of the Mexican landgrants.

After Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821, Alta California’s residents – the “Californios” – lived far from Mexico City’s bureaucracy. Over time, they became free thinkers and self-governed. They experienced a major social evolution similar to the 13 American colonies evolution away from Britain in the 18th century.

Prior to 1821, the Spanish crown had given few large tracts of land to loyal citizens who had settled in Alta California. But during the quarter century of Mexican governance, far more land grants were established. In his book “Santa Clara County Ranchos,” local historian Clyde Arbuckle estimated more than 90 percent of all land grants originated during the 24 years before California became U.S. territory in 1846.

“Spanish concessions usually represented reward for military service, but Mexico’s land laws virtually opened the field to all comers,” Arbuckle wrote. “Any reputable Mexican citizen had little more to do than file an expediente and a diseño (petition and crude map) for the land he desired. This simple process, costing about $12, could obtain for him anything from a house lot a few feet square to a rancho of 11 square leagues (48,818 acres.)”

In the mid 1830s, Hernandez hungered to be a land baron. He certainly couldn’t help but notice how Governor Jose Figueroa in 1834 had granted Carlos Castro more than 22,000 acres of land that was known as Rancho San Francisco de las Llagas (what’s now an area surrounding the community of San Martin). Also in 1834, Figueroa granted Juan Alvirez nearly 20,000 acres in an area between what’s now Morgan Hill and the village of Coyote. Alvirez’s grant was called Rancho de Laguna Seca.

Hernandez petitioned for the smaller piece of land in between these two Mexican estates. This scenic expanse of 8,927 acres was shadowed at sunset by a conical hill on the western edge of the valley (a hill now known as “El Toro”) and extended far into the mountain range on the eastern side. The Llagas Creek meandered through the tranquil setting.

“Groves of oaks then carpeted vast expanses of level terrain,” the historian wrote. “Venerable sycamores and willows marked watercourses and swampy areas. Deer, elk, bear and other wild animals mingled with herds of long-horned cattle, and seemingly endless flights of ducks and geese cast acres of shadow upon the earth.”

In 1835, Figueroa granted Hernandez title to the property. Hernandez called his new estate Rancho Ojo de Agua de la Coche – Sow’s Spring Ranch. Perhaps he had seen wild California pigs drinking at the springs somewhere on the property.

If Hernandez’s ranch is typical of the Californio estates during Mexican rule, it would have been a pleasant place to live. The Hernandez family lived in an adobe home made from clay mud. “An adobe home was ideally suited to the California climate,” according to the history book “The Story of the Great American West.” “They were warm in the winter and cool in the summer. Many rancho homes were built around a patio that was used to cook and to host fiestas.”

The day began with morning prayers, followed by a hearty Mexican breakfast. And then the men and women went to work. Hernandez’s rancho, like the others, would have focused much of its enterprise on raising long-horn cattle. After the cattle were slaughtered, the ranchers would prepare their hides and tallow and transport these to the port of Alviso to trade for manufactured goods brought by ships from the East Coast of the United States.

The hospitable Hernandez would gladly welcome weary travelers heading north or south along the El Camino Real (now Monterey Highway) that passed through the western section of his property. Californios were well-known for providing food and lodging.

“Their generosity was great, everything they had being at the disposal of friend or stranger,” wrote Eugene Sawyer in his book “The History of Santa Clara County.”

Hernandez’s life was a balance between hard work, social functions, and a devotion to his Catholic faith. “Socially, they loved pleasure, spending most of their time in music and dancing,” Sawyer wrote. “Indeed such was their passion for the latter that their horses were trained to curvet in time to the tunes of the guitar.”

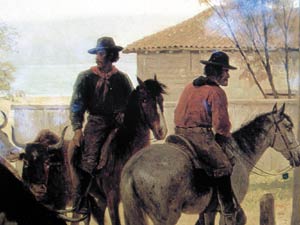

Men like Hernandez were expert horseback riders and handy with a lasso. Sometimes, if a grizzly bear wandered onto the rancho, the men would use their ropes to capture it. Then they would place the wild creature in a pit with a bull and watch the two animals fight, betting on the outcome.

Hernandez’s ownership of Rancho Ojo de Agua de la Coche was a short one. After the American conquest of California, he sold the property to the Irish immigrant Martin Murphy, Sr. The land eventually went to Murphy’s son Daniel Murphy who passed it on to daughter Diana. Diana’s husband Hiram Morgan Hill would give his name to a village here.

Guadalupe Vallejo, a Californio of Santa Clara Valley, wrote about the days of the local ranchos in a December 1890 Century Magazine essay. He recalled: “It seems to me that there never was a more peaceful or happy people on the face of the earth than the Spanish, Mexican and Indian population of Alta California before the American conquest.”

Mexican landgrant owner Juan Maria Hernandez can count himself among those happy people.

californio ranchos

Alta California was still a frontier in the 1820s through he mid 1840s, the period of the Mexican landgrant. Its residents were self-sufficient. They developed a style of life and government independent of Mexico.

There were less than 50 Californio families living in the San Francisco Bay Area at the time. They were closely connected by blood and marriage.

Rancheros such as Juan Maria Hernandez had a relatively comfortable life raising cattle, wheat and produce. After butchering the meat, they dried the hides and turned them into 23-pound “leather dollars” to be bartered for manufactured good. The hides were loaded into American ships at the port of Alviso and transported back to New England to make boots and shoes and leather goods.

The hardest workers on Californio ranchos, such as the one owned by Juan Maria Hernandez, were the “vaqueros.” Usually, they were Native Americans who worked as herdsmen. Although Spanish colonial law forbade Indians from riding horses, many mission padres winked at the rule and taught the natives how to ride to work the livestock.

Mexican California’s “vaqueros” are considered America’s first “cowboys.” They originated the clothing, techniques and terminology used later by the Anglo cowboys who roamed the West. (Linguistically, the word “vaquero” evolved into the term “buckaroo.”)