It’s been more than 150 years since Union soldiers landed in Galveston, Texas, to officially declare slavery abolished, a long two and a half years afterPresident Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law. It was Friday, June 19, 1865, the first celebration commemorating an end to slavery, which would later become known as Juneteenth.

Still, the majority of Americans are unaware of Juneteenth and its relevance in African American culture. Only in the last 50 years, following the civil rights movement, has its observance seen a resurgence.

Despite having legal rights as “free citizens,” the obstacles blacks faced would continue.

Living in a post-slavery era didn’t mean blacks had an even playing field. And yet there are stories of prominent African Americans having overcome great odds.

One gentleman named Sam McDonald is an example of such success. McDonald was born free in 1884 in Monroe, Louisiana, and was part of one of the first African American families in Gilroy.

In an interview at the Gilroy Historical Museum, Gilroy native Mack Sacco shares the life of this black pioneer in Gilroy and his experience knowing McDonald while he was a child in the 1940s. As Sacco grew into adulthood and finished a career in working in nonprofits across the globe, he became more intrigued by the personal story of this man he once knew in his youth. Sacco recalls a man who made an indelible mark on his life, although he’d known him only a short time. The excitement with which he recalls McDonald is palpable.

McDonald’s father, a Methodist minister, decided to try his hand at agriculture and arranged to move from Louisiana in 1890 to pursue sugar beet farming in Southern California with his wife and two sons.

After intensive monoculture left the region’s soil depleted, they planned to head north to Gilroy in 1897. McDonald’s mother had passed and he traveled along with his father and brother to find new beginnings. They took up in Old Gilroy, near Soap Lake, an intermittent lake in what is now known as the Pajaro River floodplain. They were among the first black families to live in Gilroy. But, Sacco says, their stay in Gilroy was brief. After their crops went bust, they made ends meet by working at the old Gubser Dairy off Frazier Lake Road. McDonald also learned much about dairy farming and raising horses during his time in the South Valley. The McDonalds stayed in the area for three years and they were well-received by the community. McDonald enjoyed an education up to the seventh grade, which was the extent of his formal schooling, according to an autobiography in the Stanford Press publication, Sam McDonald’s Farm.

The family headed toward Washington. When the trio crossed the border into Oregon, McDonald, then 16, told his father and brother that he wanted to stay in California. It was there that he left them and returned to make his life in the Santa Clara Valley.

McDonald had trouble finding work because he was so young and “at once became 21.” He got a job working on a steamboat that would travel in and around the Sacramento area. Eventually, McDonald made his way back to the Santa Clara Valley and Sacco says he heard they were hiring at the horse farm at Stanford University. McDonald became a teamster and in 1903 began working as a ground superintendent at Stanford.

He was known as an expert at preparing the surfaces of athletic areas, says Sacco. “He was like a consultant. He would consult all over the United States.”

McDonald’s contribution to athletics was far-reaching; it’s still visible today in the signature criss-cross pattern mowed into lawns so well known to football fans.

Sacco, who met McDonald when he was a patient at the Stanford Home for Convalescent Children, says McDonald had a strong relationship with the “Con Home,” as it was called. Sacco had been treated for rheumatic fever and lived in the home from age five to age eight. From 1947 to 1949, Sacco recalls McDonald came in to see him everyday and would spend hours visiting with the children.

“People would come in and do lots of projects with us and [McDonald was] one of the people that would show up and talk to us and sing to us.”

McDonald lived on the Stanford campus for the rest of his life, Sacco says. He got permission to build on the property and he lived there when he was a grounds administrator. Sacco remembers McDonald had about 400 sheep that would help maintain the grounds, where he also operated a dairy.

“He was just one of those people that just stood out,” he says. Sacco fondly remembers partaking in a barbecue every year on campus and that McDonald would prepare and serve lamb. McDonald had planted a victory garden to feed the children in the “Con Home.” Any of the proceeds from the barbecue would help support the children.

Sacco says that there were so few blacks in the area at the time and McDonald gained people’s respect. He was the first African American appointed as an administrator of a major university. He was responsible for all of the athletic grounds. “At one point they gave him a part-time job for security at the games and he would hire off-duty police officers to be at the games and keep order,” says Sacco.

During his career at Stanford, McDonald also purchased over 400 acres in La Honda, where he was an active community member on the weekends. McDonald was also a steward of that acreage and wanted to maintain it as an animal refuge. He created a wildlife sanctuary and refused to allow logging on his property.

McDonald was well liked and visited with many dignitaries, even Stanford graduate, President Herbert Hoover and the first lady, Lou Henry Hoover, who, McDonald writes, would meet with him to discuss gardening and farming.

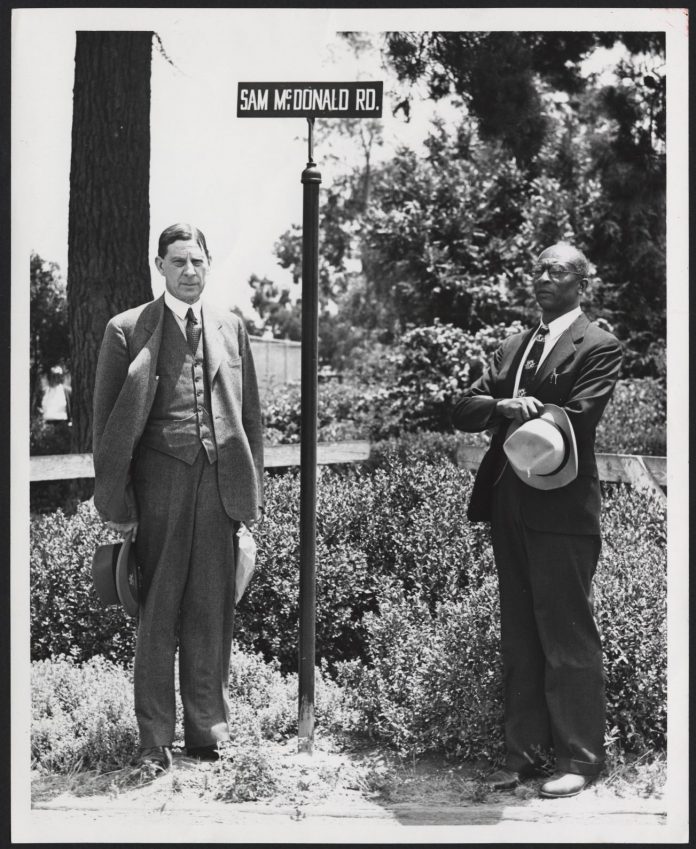

McDonald was held in such high esteem that in 1941, a road was named after him on the Stanford campus. While he was alive, Stanford President Ray Lyman Wilbur praised McDonald’s popularity. “I wouldn’t want to run against Sam for president because I’d be sure to lose,” he said.

McDonald is remembered as a smart business person, who lived as a modest man and died a bachelor.

It’s people like Mack Sacco who have maintained a legacy—a present-day connection to the past—and whose work allows us the chance to preserve our local history. They provide a view through a window in time to the everyday lives of historical figures.

In Santa Clara Valley, in McDonald’s day, the color line was not absent, but it was far more subtle than in the South. In San Jose and the valley as a whole, de facto racial discrimination, while without legal standing, was institutionalized and pervasive. This included redlining, which kept African Americans restricted to certain communities. Still, according to UC-Santa Barbara scholar Clyde Woods who wrote: Black California Dreamin’: The Crises of California’s African-American Communities, professionals and entrepreneurs like McDonald, made up a small portion of the African American community that was unparalleled in the United States.

This year marks the 35th Juneteenth celebration for the city of San Jose and the 66th anniversary for the celebration in San Francisco.

Milan Balinton, executive director for the African American Community Service Agency in San Jose, which puts on the Juneteenth celebration as part of bayareajuneteenth.org, says the festival originated as an African American community event, but that he considers it a festival for all people seeking freedom. He says that through the civil rights movement, African Americans established themselves as selfless pioneers, “today we try to make way for senior citizens, women, children and all people to pursue the American Dream.”

<

66th Annual San Francisco Juneteenth

<

Saturday, June 18, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

<

Fillmore Street, between Turk and Sutter streets

<

With entertainment on 5 stages, including a tribute to Prince

<

<

35th Annual San Jose Juneteenth in the Park

<

Saturday and Sunday, June 18-19, noon to 7 p.m.

<

Discovery Meadows

<

180 Woz Way, San Jose

<