Jim Chadsey has about three hours of stories he can tell you as

he escorts you through the Chitactac-Adams Heritage County Park.

Unfortunately, last Thursday he only had 20 minutes.

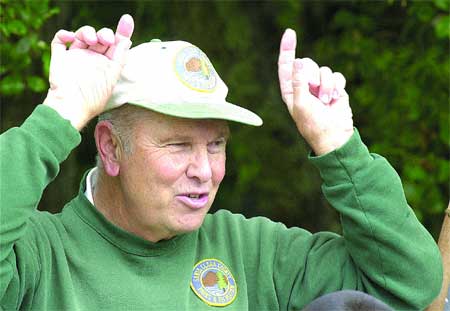

Jim Chadsey has about three hours of stories he can tell you as he escorts you through the Chitactac-Adams Heritage County Park. Unfortunately, last Thursday he only had 20 minutes.

With a pack of second-graders from Glen View Elementary School working to keep up, Chadsey did the best he could to get to each informational table to talk to the children about the lives of the Ohlone Indians, who lived here about 3,000 years ago and left only petroglyphs and mortars as a sign they were here. He teaches them to respect the park and especially the worn petroglyphs the Indians drew on the rocks thousands of years ago.

“If you erase one, you can never bring it back,” he said to the children. “Even if you know how to make a petroglyph, you can’t bring back the songs and the prayers.”

While the children in the tour group actually were at the park with their teachers Barbara Park and Karen Oneto to study steelhead trout at the park, the short tour was added to their field trip. For Chadsey, it was just another opportunity to teach children what Indian life was all about.

“I was born on a Navajo reservation, and I lived with the Apache, Rosebud Sioux, Crow and Flathead,” explained Chadsey, whose father was the principal of schools for Indian reservations, a job that forced him to move often as the family lived in New Mexico, Arizona, South Dakota and Montana. “I grew up there and went to school. I lived with them and played with them. What I bring here is my general knowledge of the people. What I teach here is not what the books say, but what the people really were like. There’s a lot of misconceptions.”

Those misconceptions are something that the 69-year-old has worked to change ever since he came to the park when it opened five years ago to act as the site host and docent. He has lived at the park in his travel trailer on and off since he began volunteering full-time at the park.

But last Thursday marked Chadsey’s last official program at Chitactac – at least for now.

“I’ve been here since the park opened, on and off,” said Chadsey, who has called the west end of the Grand Canyon his home since 1967, but has mainly lived out of an recreational vehicle and has traveled the country, spending most of his time at Chitactac. “I come and I go because I’m retired now. Everywhere I go I’ve got my house, but when I’m home, I’ve got all that extra junk.”

Chadsey left early this week to return to his Arizona home to take care of family business and tie up some loose ends. But he says he may return some day. He can’t seem to leave Chitactac full time – he’s left a few times before and always has returned.

“I’m pretty sure I’ll be back,” he said.

Meanwhile, Park Interpreter Chris Carson and the other volunteers that spend their time at Chitactac-Adams Heritage County Park will have to find a way to replace a man who spent hours a day talking with visitors, telling stories and picking up any trash left behind by the visitors.

“He’s irreplaceable. We’re going to miss him,” Carson said. “He’s been a great asset to us – we hope he’ll be back.”

Chadsey also has been a big part of the turnaround of Chitactac. When he first started at the park, it was more or less a trashing ground for its patrons and often there were cases of vandalism and graffiti. Now, with a lot of hard work and telling people to take care of their park, Chitactac is a very clean and safe park. Chadsey walks the park five to 10 times a day to make sure there isn’t any trash left around.

“Yesterday I only found two pieces of paper that people left all day,” he said.

About 120 to 150 students, teachers and parents come their way to the park each week, and Chadsey walks them through the park while carrying with him a walking stick made of the rib of a dried up saguaro cactus, with actual Indian tradebeads on it that were found under a San Francisco home – it was a gift one of the last times he left the park. Chadsey would then try to show people not only what the Indians’ way of life was like but why they did many things that have led to what he says is an inaccurate stereotype.

“I try to take people back in time, before the white man,” he said. “When you start to figure out everything that went on, you realize these were very smart people. They weren’t naked savages, they were very intelligent people – very religious, high standards and ethics. People being different doesn’t make them wrong. I try to educate people why this is so important.”

As he decsribed the Ohlone village to the park visitors, Chadsey explained a game young boys played. A boy would roll a hoop along the ground and another boy would throw a spear through the hoop to get points. He explained to the children how the game taught young Indians how to hunt. Chadsey also talked to the kids about how local bay trees were important to tribe, which used the leaves as medicine and ate its avocado-like fruits.

“You had to use what you had,” he explained.

Chadsey said that regardless of one’s background, people should study their families’ traditions and pass them down to their children – especially Native American families.

“Learn and teach your children,” he said. “If you don’t, the history will be lost. And if people aren’t Native Americans, find out about your people.

“I’m trying to bring back their culture. It doesn’t make you any richer or poorer, and smarter or dumber, but you’ll know where you came from.”

That is a message that the other volunteers will try to continue to instill in the visitors of Chitactac Park, and meanwhile they will look forward to Chadsey’s return.

“He’s put his heart and soul into this place,” Carson said. “He’ll be dearly missed.”