Andreas Heinrich was just another physics graduate student 20

years ago when he called IBM fellow and world-renowned

nanoscientist Don Eigler directly.

Andreas Heinrich was just another physics graduate student 20 years ago when he called IBM fellow and world-renowned nanoscientist Don Eigler directly.

“I really wanted to come here,” Heinrich said about IBM, who produce the premier groups of scientists in the world, he said. When Heinrich called, he was in his mid-20s in his homeland of Germany working on one of his three college degrees in physics.

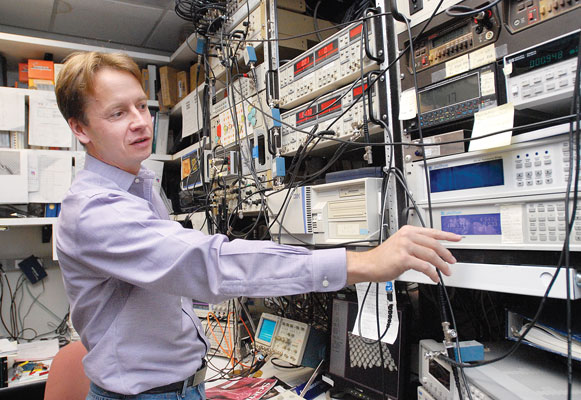

“So, Don said ‘no,'” Heinrich stopped to laugh, “oh, that sucks,” he said to himself. Wires of every color and thickness dangled wildly around him as he crossed and uncrossed his legs from a swivel chair in his lab. It’s a room packed floor to ceiling with space-age looking machines. Aluminum foil is essential here, though not for baking.

Heinrich called again. Eigler said “no,” again. “I thought, ‘Oh, that really sucks,’ ” he said. “This is really like a little guy coming to the big guy.”

The third time, Eigler didn’t say no quite as harshly. He asked Heinrich to find some external funding and IBM would pay the rest.

That was 12 years ago.

Since then, Heinrich’s contribution to IBM’s nanoscience research has scooted he and his team into the world spotlight. Last month, they published a paper in the international journal “Science” that’s been deemed a breakthrough among those who know and been written about in The New York Times. Their addition to the scanning tunneling microscope – the one that put IBM scientists on the map when they were awarded with a Nobel Prize in the 1980s – enables the ability to record, study and visualize the magnetism of individual atoms at staggering speeds: one million times faster than previously possible.

The technology could be used in solar energy, computer data storage and quantum computing disciplines to effectively store more information than ever before.

Heinrich’s team has revised the way atoms are measured using a short voltage pulse that excites an atom, followed by a lower voltage pulse to read the atom’s magnetic spin. It’s recorded, for the first time, at even higher speeds and with images in high resolution. The research is indicative of figuring out exactly how many atoms are needed to store a single bit of information. In time, it could be applicable to everyday uses beyond what it could mean for super-computers; an iPod could hold a million songs, for example.

Heinrich has lived in Morgan Hill since he landed the IBM job in 1998 at the Almaden Research Center – a science microcosm at the top of winding road through several security gates in the Almaden Hills. He met his wife while studying abroad at the University of California, San Diego where he did undergraduate research – “That’s basically how I got hooked to the United States” – and now the two live in Holiday Lake Estates and raise their Nordstrom Elementary second-grade daughter Sierra and son Toby, 4.

Post-doctorates have a two, maybe three, year window to make a name for themselves in the science world by publishing results in various science journals – the most premier being “Science” and a British journal “Nature.” Heinrich got a buzz to build a tool so advanced that it took three years just to construct.

“It made it essentially impossible to get results in time. It was a very risky project to take on. In hindsight, it was pretty stupid actually. You always think you can do it twice as fast. But, no risk, no fun,” he said.

It did work out for Heinrich. The recent “Science” publication is the sixth research paper that he’s been a part of.

“This breakthrough allows us – for the first time – to understand how long information can be stored in an individual atom. Beyond this, the technique has great potential because it is applicable to many types of physics happening on the nanoscale,” said Sebastian Loth, Heinrich’s colleague.

The stuff of “Big Bang Theory” that character Sheldon often cites – such as quantum mechanics or Moore’s Law – don’t function very well as small-talk at most parties, but for Heinrich and other nanoscientists it’s what stimulates the brain day in and day out. The TV show is uber popular among physicists, too, Heinrich said. “If you look at that show, it’s pretty amazingly accurate.”

When he’s not watching “Big Bang” or traveling with his family to Germany every year to visit or fiddling with the atoms in his lab, Heinrich makes wine. He and his neighbors partnered to form Copper Hill Winery, crushing grapes they buy locally and fermenting them at a neighbor’s home, then throwing bottling parties to cork and of course uncork the fruits of their labor. It’s just another extension of Heinrich’s affinity for how things work. Tinkering and tottering with machines has been a lifelong hobby.

“If you ask my mom, I would always take things apart. I would take the radio and next thing you know, the radio is in pieces. When she heard I was building this complicated machine, she didn’t think I could do this – actually assemble something, not just disassemble,” he said.

How does Heinrich explain what he does to his young children?

They know what atoms are, he said, as he turned to grab a red ball on the desk behind him, probably a billion times or more larger than the single atom it represents.

He tells a story that make his eyes smile, “It’s a great one,” Heinrich says. At a conference in Aspen, Colo. that Heinrich organized for IBM, he invited Eigler to give a public lecture for the Aspen community, something they often do amid the scientist-only conferences – and skiing.

Sierra raised her hand, without any prompt from Heinrich or her mother, and asked Eigler, “So Don, how do these atoms stick together?”

“She could barely see over the seats,” Heinrich laughs. “Don thinks about it and gives her an answer a little bit higher than her level. So he says, ‘No, that wasn’t a good answer.’ ” Heinrich stops, timing the punch line. “Atoms are sticky,” he said. “It was great. She said ‘OK, atoms are sticky.’ She understood that,” Heinrich said.

The goal is to continue to produce research worthy of big publications like those he’s already helped pen in “Science.”

“If we can publish something in these high-stake publications, then people like you are interested in us,” Heinrich said, “IBM and science will receive more visibility in the general community.” After all, Heinrich’s just your average, everyday physicist.

“If the public doesn’t know about science, it will fade. I don’t want to see that happen,” he said.