A visit to the police station with a child high on drugs is a

parent’s nightmare, but Kristina Ortiz claims she’s had this

experience several times after picking up her daughter at Sobrato

High School.

Morgan Hill

A visit to the police station with a child high on drugs is a parent’s nightmare, but Kristina Ortiz claims she’s had this experience several times after picking up her daughter at Sobrato High School.

“I’m extremely upset, and I just don’t know what they’re doing about it,” she said.

Ortiz wants school officials to get rid of the drugs on the campus.

The district has a zero-tolerance drug policy and students found to be under the influence, in possession of or selling drugs on campus are reported to the police, and repeated use or possession on campus will lead to a recommendation for expulsion.

Regardless of the policy, Ortiz emphasized that drugs are prevalent at Sobrato.

Sobrato Principal Debbie Padilla said Ortiz has also asked for the school to hold mandatory semester-long drug education classes for all students, but Padilla said information about the dangers of drugs is given to students in a variety of formats in several different classes already.

“We do have drug component in health, which students have in PE, and in biology,” she said. “We also give students information regarding drug use during Red Ribbon Week.”

Padilla, who came to Sobrato this year from San Benito High School in Hollister, said she did not think Sobrato had more of a drug problem than her previous school or other schools.

“I’ve never been to a (high school) campus that is completely drug-free,” she said. “Until we can get our community drug-free, it’s going to be hard to get our schools drug-free.”

School resource police officer Mike Nelsen said the problem on campus is not only the ecstasy pills that Ortiz’s daughter allegedly took, but also other drugs on campus, including alcohol. Sometimes the clear liquid kids are sipping from plastic bottles is not water, he added.

If the students were more cooperative about telling who is selling drugs to them, it would be easier to get drugs off campus, he said.

“We don’t have a crystal ball. We have to have some information,” he said. “We can’t do random locker searches.”

Bob Davis, coordinator of student services for the district, said the district will act on information received but not violate student rights.

“We do have to protect student rights,” he said. “There are some impacted areas that actually have a lot of electronic equipment that they use, some on a daily basis, but we’re not in that kind of environment in Morgan Hill … however, we do actively work to intercept and investigate every incident.”

Nelsen said students who may have information about drug use or drug sales can remain anonymous.

Padilla agreed: “We all need to work together … We can keep the identities of students who give us information anonymous, students can also give the information to their parents and have their parents call in and give a tip. It takes everyone, just like with downtown Morgan Hill, it’s only as safe as people make it.”

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University conducted a teen survey this year and in August released results that show Sobrato is not the only campus where drugs are available.

According to the survey, 80 percent of high school students and 44 percent of middle school students attend “drug-infested” schools. The center defines a drug-infested school as one where the students surveyed say they have personally witnessed illegal drug use, illegal drug dealing, illegal drug possession, or students drunk or high.

The survey also reveals that during the past five years, the proportion of students attending drug-infested schools has jumped 39 percent for high school students and 63 percent for middle school students.

High school staffs and district officials are aware of the problem, Padilla said, and are taking a variety of steps to improve the situation.

Besides Nelsen’s presence on campus, Padilla said, there are staff members who patrol the school during lunch and brunch periods, as well as other times during the day. The staff has recently received training from Nelsen in recognizing drugs and their effects, and regularly brings police into situations on campus.

“Perhaps that’s why there is the perception that are more drugs here, because the administration has been very proactive about bringing us in,” Nelsen said.

Parents can be proactive, too, by remembering they are the ones in control when confronted with a drug-abusing child. Some parents, he said, seem afraid to take the drastic steps necessary in some cases, like searching their kids’ rooms, taking the door off the hinges, not letting them associate with friends who are consuming illegal substances.

Some people believe outsiders or former students are coming onto Sobrato’s campus to sell students drugs, Ortiz said.

Padilla said Sobrato staff members are alert to the possibility.

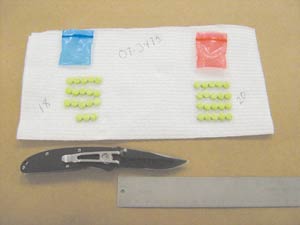

Nelsen believes it’s mostly the students themselves providing drugs to other students. Recently, a male Sobrato student was arrested after police found 38 tablets of ecstasy and a knife in his possession.