A full-sized American flag sways gentlyoutside Lawson Sakai’s front door, and several miniature versions decorate his living room. Another big one is folded into a triangular military display box on his mantle. The mouse pad next to his computer is red, white and blue.

The 92-year-old Sakai, a Japanese-American, remains deeply in love with a country that shunned him at 18, when he tried to enlist in the military after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

“They called me an ‘enemy alien’ and said I wasn’t an American anymore,” says the former Gilroy resident now living in Morgan Hill, who was born and reared in Los Angeles. “It was just that blunt.”

Sakai was angry and hurt by the rejection, part of a national security panic that infamously resulted the three-year internment of at least 110,000 “Issei”—first-generation Japanese who had immigrated to North America.

Sixteen months later, as the war accelerated and the American military changed its rules, Sakai—by then a student at Mesa College in Grand Junction, Colorado—tried again. This time he was accepted and assigned to the U.S. Army’s 442nd regimental combat team, an all Japanese-American unit that would be remembered among the most courageous and heroic in history.

More than seven decades later, Sakai has a crystal-clear memory of the brutal battles he survived, including the liberation of Bruyères, the rescue of the “Lost

Battalion,” and the battle of the Gothic Line.

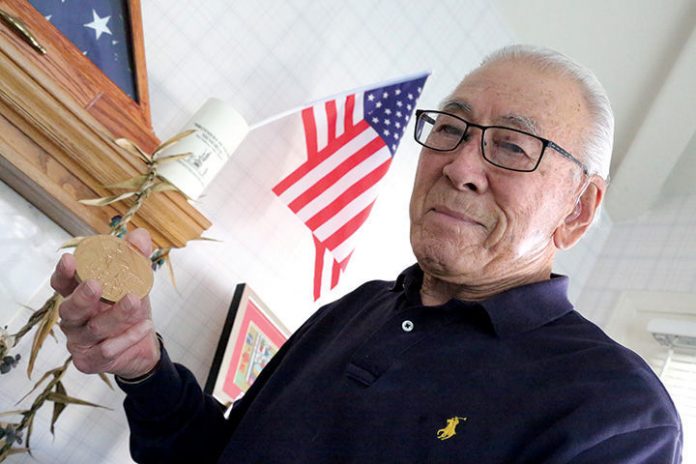

On Feb. 13, Sakai was honored by the Consul General of Japan, Jun Yamada, with the Japan Foreign Ministry award, in a meeting of the Friends and Family of Nisei Veterans in Morgan Hill. (“Nisei” are children born in a foreign country to Japanese-born immigrants.) The award is presented annually to “individuals and groups with outstanding achievements in the promotion of friendship between Japan and the United States,” according to the Consulate General website.

Though he smiles and laughs easily today, he says he still has “crazy dreams” about his wartime experiences, and occasionally feels pain or itching in areas of his body that were wounded in battle. He was hit once by grenade fragments, a second time by shrapnel from an artillery shell.

One of his most harrowing moments, though, came as he trudged through France’s Vosges Mountains with the 442nd’s 2nd Battalion in search of the Lost Battalion.

“We were attacking, going uphill, moving pretty quickly, when a German soldier popped up from a foxhole right in front of me. I just heard pop! pop! pop! pop! and remember thinking, ‘I’m dead.’ But nothing happened. He missed.”

Sakai leaped forward, grabbed his assailant, and fought hand to hand. When the Nazi’s helmet fell off, he realized he was fighting with a boy.

“He was maybe 14 or 15,” he remembers. “I don’t know how he missed me from point-blank range, but he did. That happened on Oct. 27, 1944. It was my 21st birthday.”

Sakai’s unit was originally deployed to Italy in May 1944, where they became part of the army’s 34th division, pushing north—“a rather pleasant invasion,” he says with a laugh, because most German forces were in France, fighting at Normandy.

“Our first combat was on July 4. The Germans opened up on us with everything—rifles, machine guns, mortars, artillery. I remember dust flying up from the ground and thinking, ‘What the hell is that?’”

The dust was kicked up by rounds from a German burp gun, a high-velocity weapon so powerful that it is virtually impossible to control.

“It recoils so violently that you can’t hold it down,” he says. “So the bullets are hitting the ground once second, then flying over your head the next, hitting the trees above where they were aiming.”

Sakai’s captain and first lieutenant were killed in that first battle. Countless others died or were wounded.

“All of us were green. None of our officers had been in combat. We didn’t have a chance,” he says. “It was broad daylight, but somehow we were able to find cover and start firing back.”

Things got worse in October 1944, when the 442nd went to France with orders to liberate Bruyères, a village surrounded by four mountains where a key railroad line was controlled by the Nazis. The mission was to take the railroad.

“We were moving through a flat area, next to the railroad tracks, when the Germans started sending everything down on us from the hills. We had no choice but to go up after them,” Sakai says.

As they ascended the mountain, the German army opened fire with 88mm anti-aircraft guns—weapons designed to shoot down planes thousands of feet in the sky.

“They mounted them on half-tracks and lowered them to shoot at infantry,” Sakai says. “The shells are screaming as they’re coming at you, blowing the trees into splinters, knocking branches off on top of you, sometimes even blowing trees in half. Guys were getting crushed. It was horrible.”

The violent, eight-day struggle took place in a frigid rainstorm, but on Oct. 23, the Americans drove the Nazis off the mountain, then flushed them out of the houses in the village.

After two days of rest, the 442nd was summoned again, this time to come to the aid of the 141st regiment of the 36th division, which had been surrounded by German troops on a mountain five miles ahead of the rest of the American forces.

“Gen. [John] Dahlquist was in a race with [Gen. George] Patton to be the first to cross the German border. He commanded the 141st to go charging in, ahead of everybody else. It was a huge mistake. The Germans just let them go, then surrounded them,” Sakai says.

Dahlquist initially sent his second and third battalions into the fray, but made no headway, so on Oct. 25, 1944, he called the 442nd to help rescue the unit, which was composed almost entirely of Texans.

“Our push took five days. We were chasing the Germans from one mountainside to another, uphill all the way. They’d get to a high point and open up on us with machine guns,” Sakai recounts. “The only way we could get them was to get close enough to throw hand grenades. Our casualties were extremely high. It was basically a ‘banzai charge,’ which is all-out, go for broke, everybody shooting, going as far as they could go, one hill after another, until they got shot down.”

The 442nd’s third battalion, which began with about 250 troops, went first. Eight men made it out.